When people think about excessive technology in schools, their minds usually go to phones. But according to a new book from neuroscientist Jared Cooney Horvath, we’re overlooking the true culprits: the laptops sitting on students’ desks. In “The Digital Delusion: How Classroom Technology Harms Our Kids’ Learning—and How to Help Them Thrive Again,” Horvath explains why consuming information through screens leads to falling performance, fractured attention, and the slow erosion of rigorous thought.

We’re proud to publish an exclusive, adapted excerpt from the book that answers an urgent question: Why, after generations of progress, are today’s children less intellectually capable than their parents? —The Editors

This might be one of the hardest truths today’s parents have to face:

Our children are less cognitively capable than we were at their age.

The daughter who once loved school, but now dreads it. The son who used to devour books, but now scrolls until midnight. Fading memory, slipping focus. Something is wrong, and many of us have felt it.

For nearly two centuries, the West experienced steady generational progress. Throughout the 20th century, IQ scores rose steadily, with each generation gaining about six points over their parents. This growth was largely driven by improved education: The more time children spent in school, the more their cognitive abilities grew.

But starting around the year 2000, something changed. For the first time in the history of standardized cognitive measurement, Generation Z is consistently scoring lower than their parents on many key measures of cognitive development—from literacy and numeracy to deep creativity and general IQ. And the early data from Generation Alpha (born after 2012) suggests the downturn isn’t slowing—it’s accelerating.

Stronger cognitive skills are linked to better health, longer life, more stable relationships, higher income, and greater life satisfaction. We need a generation capable of deep thought; kids who can grapple with nuance, hold multiple truths in tension, and creatively tackle problems that stump the greatest minds of today.

But instead of cultivating these capacities, we’re quietly undermining them. Somewhere along the way, we’ve stripped something vital from our children—and perhaps the cruelest part is, they don’t even know they’ve lost anything.

What went wrong?

Researchers like Jean Twenge and Jonathan Haidt point to smartphones and social media; tools that promote sedentary behavior and encourage isolation. Others, such as Abigail Shrier and Greg Lukianoff, argue we’ve over-medicalized childhood, treating ordinary experiences as “trauma” and shielding kids from discomfort in ways that leave them fragile and unprepared.

While these factors certainly illuminate the existing mental health crisis, they don’t fully explain the cognitive collapse. Why are so many kids learning less?

To address that, we need to look at the one place most parents still trust to support learning: school. Today, children are spending ever more hours in classrooms, yet they’re developing more slowly.

The culprit lies in the meteoric rise of educational technology.

When parents hear that schools are increasingly embracing digital technologies, many picture something familiar from their childhoods: a few dusty desktops in the library, a weekly typing lesson, maybe a chance to paste clip art into MS Paint if the teacher was feeling generous. Whatever our feelings toward computers, one thing was clear: They were always peripheral to our education.

But that image is now dangerously outdated.

Over the past two decades, educational technology has exploded from a niche supplement into a $400 billion juggernaut woven into nearly every corner of schooling. More than half of all students now use a computer at school for one to four hours each day, and a full quarter spend more than four hours on screens during a typical seven-hour school day. Researchers estimate that less than half of this time is spent actually learning, with students drifting off-task up to 38 minutes of every hour when on classroom devices.

Driving this digital surge are global tech firms that have perfected the art of harvesting data and maximizing screen time. Many educational platforms openly track behavior, build long-term profiles, and use the same engagement-driven designs that keep adults endlessly scrolling on TikTok or Instagram. The business model is to hook kids early, and create customers for life.

This has consequences. The Program for International Student Assessment (PISA) is the world’s largest standardized test. Every three years, hundreds of thousands of 15-year-old students across dozens of countries complete the exam, which assesses knowledge across math, reading, and science.

In 2012, 2015, and 2018, PISA asked students how much time they spent using digital devices during a typical school day. When those answers were compared with test scores, the results told a clear and troubling story.

The more time students spent on screens at school, the further their scores fell. On average, those who used computers for more than six hours per day scored 65 points lower than their peers who didn’t use them at all. That’s the difference between the 50th and the 24th percentile—equivalent to a two letter-grade drop.

And this wasn’t just a developing world issue. Among wealthy Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development countries, the average drop was even steeper: 67 points.

And this pattern isn’t unique to PISA. Other major national and international tests across math, science, and reading show the same trend: The more screens children use at school, the lower achievement falls.

These standardized test results are echoed across more than 25 years of academic, clinical, and classroom research, the vast majority of which points to the same conclusion: When schools replace traditional learning with digital tools, student performance declines. The evidence is broad, consistent, and difficult to ignore.

It’s one thing to know that digital tools impair learning. It’s another to understand why. Consider one of the most fundamental academic skills of all: reading.

For more than three decades, researchers have known that students comprehend and remember less when reading from screens than from paper. Yet despite this, schools continue shifting textbooks, novels, and assignments online.

Many educators assume that students will eventually adapt. But the long-term data shows the opposite. Each year, students show a slightly worsening ability to comprehend and retain what they read from screens.

Why? The answer is rooted in biology, and begins with space.

Have you ever tried to scroll back to something you’d just read on a screen, only to find you can’t locate it? You know it was there a few swipes ago, but now it’s gone. That’s not your imagination—it’s your memory system failing.

Much like a global positioning system (GPS), the hippocampus (our brain’s memory center) builds a continuous mental map of the world around us. And each time we learn something new, that memory becomes tied to a specific three-dimensional location within that map.

When we read from paper, each word occupies a fixed, physical location. If you’re reading a printout of this piece right now, this sentence exists right here—and this spatial position becomes part of the memory you’re forming. This is why readers often remember where in a book an idea appeared, even if they can’t recall the exact wording.

Digital text has no such stability. If you’re scrolling through this piece on your computer or phone, then this sentence first appeared at the bottom of your screen, is now sitting near the middle, and will soon vanish out the top. With no fixed location for ideas to attach to, the spatial scaffold that supports memory collapses.

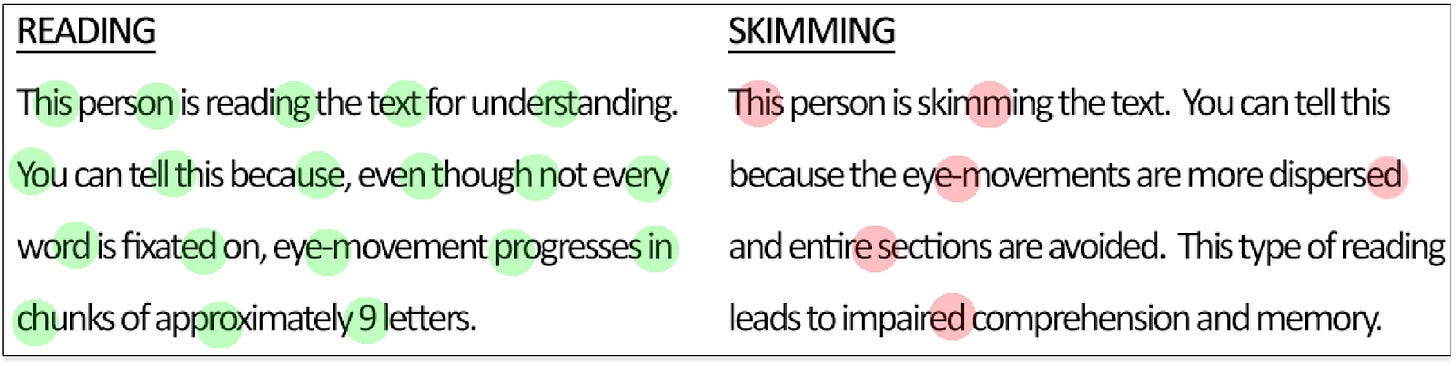

As a result, reading from screens often triggers an unconscious shift from deep comprehension to shallow skimming—glancing, scrolling, and extracting instead of truly learning.

This is one reason why scores on the PISA exam dropped so sharply after the test moved online. And it’s why the SAT, when it went digital in 2024, quietly redefined “reading comprehension” altogether. Since its inception in 1926, the SAT’s reading section has required students to comprehend a series of extended passages. The format has varied over the years, but beginning in 2016, students had to grapple with five long passages of roughly 750 words each—passages that demand sustained focus and analysis. That ended in 2024: Students are now presented with 54 short snippets of about 75 words each, followed by a single factual question about each.

We’re not adapting tools to fit our children; we’re reshaping children to fit the tools. We’re lowering the bar to conceal our kids’ shrinking capacity for comprehension.

So, what can parents, teachers, and schools do?

First, buy a printer. Reading, writing, note-taking, homework, practice problems—these all work better on paper. If families embrace this simple shift at home, it becomes far easier for schools to follow suit.

Second, allow students to opt out of ed tech. Thanks largely to the pandemic, an estimated 88 percent of U.S. public school districts now issue laptops or tablets to students. While these devices make it easier for teachers to collect assignments and generate reports, they have been shown to significantly undermine student learning. Administrative convenience should never come at the cost of cognitive development.

A few years ago, many insisted smartphone bans were impossible—yet today they’re becoming law around the world. The next step is clear: Families should be legally permitted to opt out from mandatory academic screen use. No parent should be told their child cannot attend public school unless they spend six hours a day on a device.

Third, demand evidence. Schools often justify tech purchases with glowing stories of success. You might hear about a class in Charlotte, North Carolina, using iPads to clean a river, or students in Topeka, Kansas, coding an app that saved a local business.

Unfortunately, anecdotes aren’t evidence.

Whenever a school announces a new digital tool, ask for independent, replicated research showing it improves learning. If the data doesn’t exist (or comes only from vendor-funded studies), the tool isn’t ready for classrooms.

Next, ask for internal data. Even if a tool works elsewhere, has it been tested in your school, with your students, under your conditions? No digital program should be scaled school-wide until it first proves itself in small, local trials.

Finally, if no meaningful research exists (as is true with many emerging artificial intelligence tools), ask for a clear, evidence-based rationale that answers three questions: What specific problem does this tool solve? How will it improve learning, not just logistics? Why is this the best available solution?

Any tool worthy of our children should withstand basic scrutiny. If it can’t, say no.

In the late 18th and early 19th centuries, textile weavers across England found themselves being rapidly replaced by machines. Seemingly overnight, a once highly skilled profession was reduced to low-grade piecework.

So the weavers fought back.

Under the banner of a mythical figure named Ned Ludd, they destroyed mechanized looms and burned high-tech knitting frames. History remembers these rebels as Luddites—a modern slur for anyone who dares question the supposed wonders of our digital age.

But the Luddites weren’t afraid of machines. They were afraid of what blindly adopting machines would do to the people forced to use them. Ultimately, their warning wasn’t about technology; it was about values.

Two centuries later, we face a similar dilemma. We can keep surrendering our classrooms to tools that make learning weaker, shallower, and narrower. Or we can insist that education remain grounded in deep attention, sustained effort, and real connection.

This isn’t about scrapping computers from schools; it’s about restoring rigor to the classroom. It isn’t a battle over tools; it’s a battle over values. It’s a battle over what kind of people we want our children to become.

Adapted from The Digital Delusion: How Classroom Technology Harms Our Kids’ Learning—and How to Help Them Thrive Again by Jared Cooney Horvath.